You think outdoor air is dirty? Wait until you see what the air in peoples' homes looks like

We're just barely starting to understand what dirty indoor air is doing to our minds and bodies

Talk of air pollution in the United States typically focuses exclusively on outdoor air. The EPA’s vast network of air quality monitors, for instance, track outdoor air quality, and those readings are what drive the official federal air pollution reports that inform regulatory actions.

But there’s precious little data on indoor air quality, and that’s a massive blind spot when it comes to our understanding of how the air we breathe affects our well-being. The EPA points out that “there is no nationwide monitoring network that routinely measures air quality inside a statistically valid sample of homes, schools, and office buildings.” The typical American spends something like 90 percent of her life indoors, with the bulk of that indoor time taking place in her own home.

Scientists in recent years have started to suspect that the air in our homes is likely to be even dirtier than the air outside, with unquantified but potentially significant effects on our health. Recent studies, for instance, have found that the cognitive functioning of students and office workers is impaired when exposed to elevated levels of indoor air pollution, even for a short period of time. In one study, a single burning candle emitted enough smoke pollution to lower participants’ performance on basic cognitive tests.

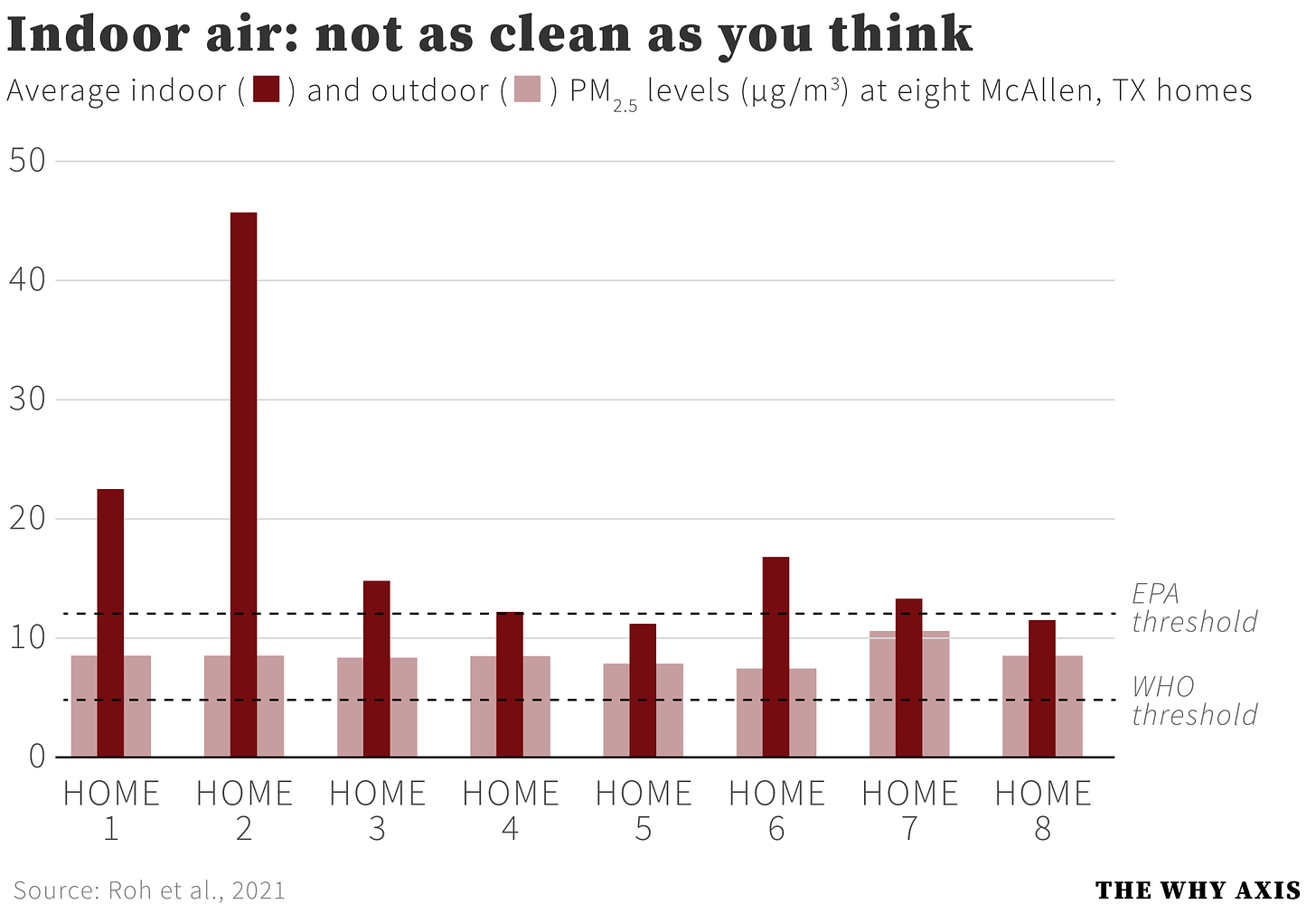

One new study, recently published in the journal Atmosphere, illustrates how relatively clean outdoor air is no guarantee of healthy air indoors. The researchers monitored the indoor air quality in eight homes in McAllen, Texas between June and September of 2020, when at least one of each household’s members were working at home due to Covid restrictions. To set the stage, here’s what outdoor air quality monitors were reading at all eight locations during the study period:

At every home, outdoor concentrations of PM2.5 — miniscule particles that are a leading driver of premature deaths due to air pollution — averaged eight to ten micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m³). That’s higher than the 5 microgram limit for annual exposure recommended by the World Health Organization, but below the more lax (and arguably outdated) 12 microgram American standard set by the EPA.

You’re probably wondering why there’s so much empty space in the chart, with the Y-axis going all the way up to 50 micrograms, right? So, let’s add the data from the indoor monitors.

Yeesh. At every location, the air inside participants’ homes was dirtier than the air without. At 6 out of the 8 sites, average indoor levels surpassed the already permissive EPA exposure limit. At one home the average level of indoor PM2.5 was 20 micrograms, or five times the WHO limit. At another, the average reading approached a whopping 50 micrograms.

To put those figures into context: California’s Central Valley has the most polluted air in the country, with parts averaging anywhere from 15 to 20 µg/m³ all year round. That’s widely viewed as a public health crisis shaving years off residents’ lives.

But at the most polluted home in this new study, the indoor air is more than twice as dirty as the outdoor air in the Central Valley.

Why is the air in some of these houses so bad? It’s not immediately apparent. “All households had electric dryers vented outside and kitchen fans, and none of their family members smoked or worked with hazardous materials on the job,” the authors explain. “Six homes had furry pets and non-carpeted floors... Seven families used electronic stoves and bathroom fans, and three households had air purifiers. Most households rarely opened windows for ventilation and only three households cleaned their floors regularly using a vacuum cleaner.”

But none of these factors really correlate with the observed discrepancies in indoor air quality. Home #2, for instance, had no pets, no carpeting, an electric stove, and the residents reported regularly opening windows for ventilation and using an air purifier. The authors told me the participant didn’t track their daily activities during the study period, so it’s not clear why their numbers were so high.

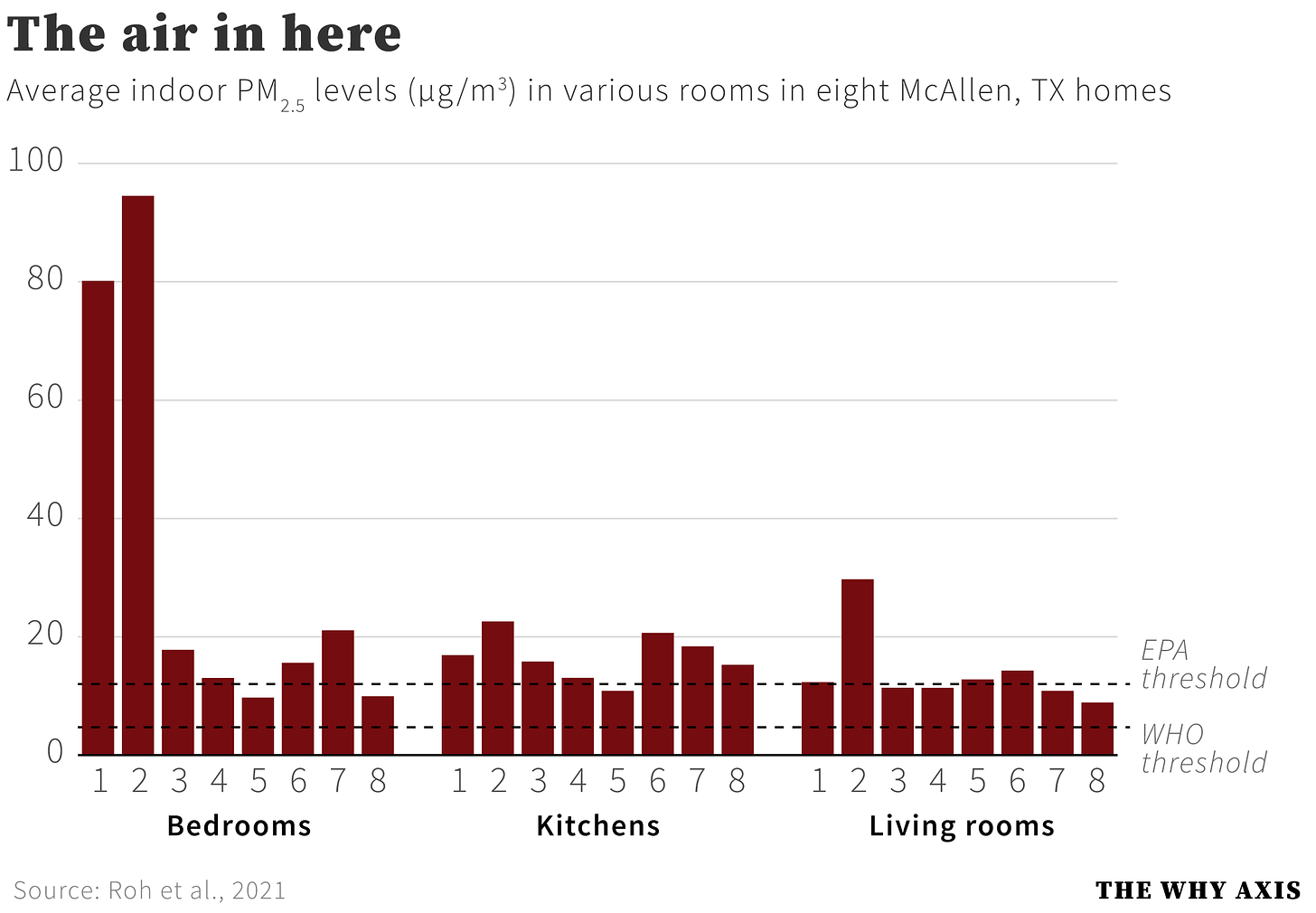

They also found evidence that air tends to be dirtier in some rooms than in others.

Bedrooms and kitchens, for instance, tended to have higher PM2.5 levels than living rooms. The average in two of the participants’ bedrooms surpassed an astonishing 80 micrograms per cubic meter during the months of the study. The long-term health impacts of breathing in that type of pollution night after night? Essentially unstudied and unknown — but not likely to be great, given everything else we know about PM2.5 exposure.

One thing to keep in mind is that PM2.5 is defined solely on the basis of particle size — if it’s smaller than 2.5 microns in width it’s classified as PM2.5, regardless of what it is or where it came from. It may be the case that PM2.5 encountered indoors is compositionally very different than outdoor PM2.5, which would suggest a different health risk profile — but again, unfortunately, we don’t know much about this yet.

“We understand far more [about] outdoor PM2.5,” said Alejandro Moreno-Rangel, one of the study authors. “Hence it is traditionally seen as a 'higher' risk, but that does not mean that indoor PM2.5 cannot have the same impacts.”

One other thing to point out — the study monitored pre-pandemic air quality at all eight individuals’ places of work. The office air was better across the board, even during the pre-pandemic period when workplaces were full of people. That likely owes to the sophisticated HVAC systems used in most modern offices, which filter the air and exhaust dirty air outdoors. Most homes aren’t equipped with that level of whole-building air filtration.

By design, this study raises far more questions than it answers. What are the health and cognitive effects of that relatively dirty indoor air? How do peoples’ daily activities affect the air quality in their homes? What does a home’s air pollution profile look like over a whole year, rather than just a single season? How does outdoor climate affect indoor air quality? What makes the air in some rooms cleaner than in others? What sorts of people are most sensitive to the effects of dirty indoor air?

As they say in academia, “more research is needed.”

Last fall my wife and I went under a contract for a house, and since she has chronic health issues, we didn't skip inspection (which has become increasingly common in this crazy market).

Since I worked, she was in charge of overseeing inspections and spent a lot of time at the house. Over the several days she spent there, she started to develop a persistent cough.

Long story short, the inspections found high mold counts and meth usage (not production) and ultimately the deal fell through. My wife had to get an albuterol inhaler and since then she bought a compact air quality monitor.

Let me tell you something: the air quality monitor has saved us a lot of time by rejecting houses that we normally would have put an offer on and inspected. Colorado is very dry, and homeowners have the mistaken impression that mold is not an issue here (it is).

Anyway, thanks for writing on this very under-appreciated topic! It would be interesting if someone delved deeper and analyze what kind of particles end up in indoor air and what we can do about it.

Very interesting.