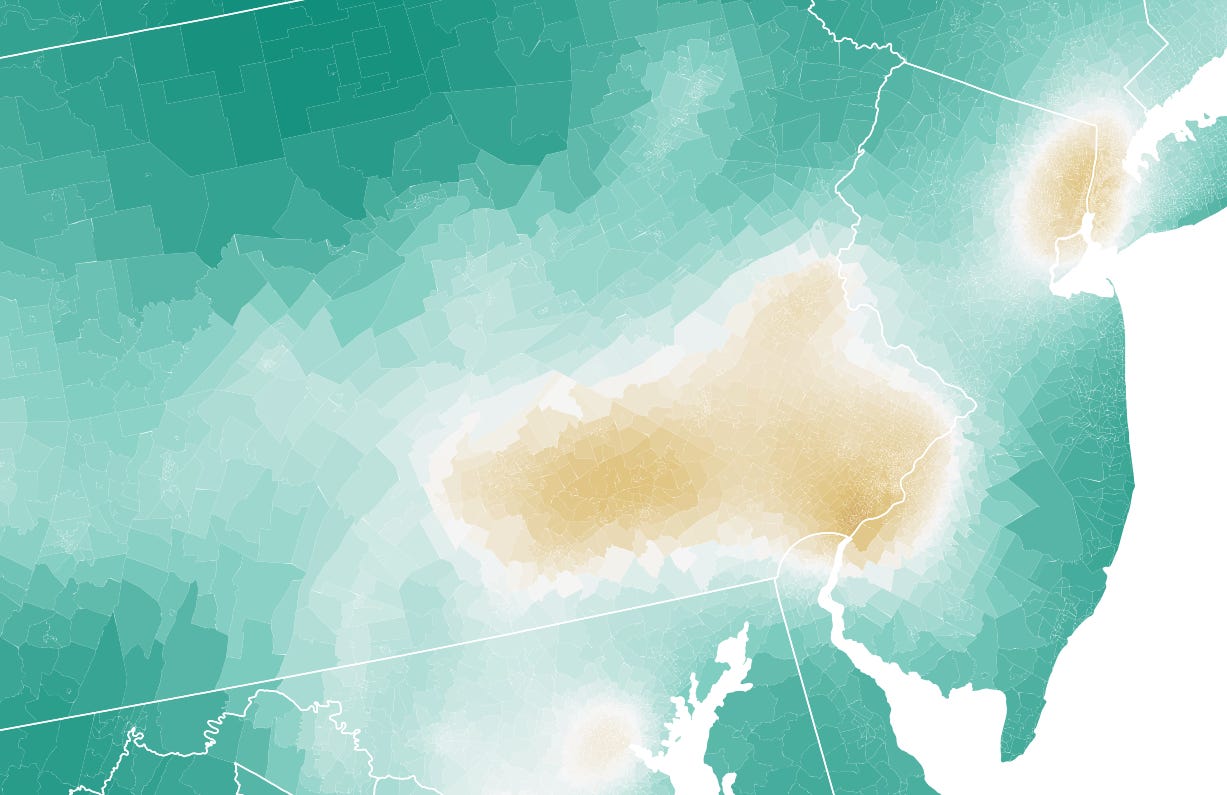

Map: Where America's air is the dirtiest

In some places, annual average pollutant levels surpass WHO limits for single-day exposure.

We’re talking about dirty air this month at The Why Axis. One of the first things we need to do is to get the literal lay of the land, in order to answer a really basic question: which places in the U.S. have the dirtiest air?

For simplicity’s sake, we’re going to answer this by measuring average annual fine particle pollution, or what’s known as PM2.5. This stuff is of particular (get it?) concern to regulators because its small enough to get inhaled deep into the lungs, where it can enter the blood stream and even the brain. All manner of health problems ensue.

Average annual levels of PM2.5 form the basis of a number of environmental regulations and guidelines. The EPA, for instance, says that annual levels of this pollutant shouldn’t surpass 12 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m³). The World Health Organization recently slashed its limit down to 5 µg/m³, a nod to all the new research showing that this stuff is a lot worse for us than previously expected. The WHO further says that nobody should be exposed to levels of PM2.5 higher than 15 µg/m³ for more than 24 hours.

So, here’s the bad news: there are still places in the U.S. where average PM2.5 levels surpass that 24-hour 15 µg/m³ limit all year round.