On Christmas Eve, John Klasen drove his truck onto the ice of northern Minnesota’s Lake Bemidji with his longtime partner Marcy Binkley. The pair were planning to do some ice fishing off Diamond Point Park, near the Bemidji State University campus.

A Vietnam veteran, John had been born and raised in northern Minnesota. He was an experienced hunter and fisher who loved the outdoors, according to news reports. He knew his way around the ice, and before he and Marcy left that day they told family members it was about a foot thick where they were headed — enough to support the weight of a medium truck.

But ice, as state officials are fond of telling people, is never 100 percent safe. About 300 feet away from shore they hit a thin patch, just four or five inches thick. The ice broke and the truck went through.

When emergency personnel arrived on the scene shortly thereafter they found Marcy on the surface — she had managed to escape the truck and pull herself out of the water. But John was still submerged, and had to be recovered by firefighters wearing cold water immersion suits. He died later that evening at a regional hospital.

Ice fishing is more or less synonymous with Minnesota winters. Tiny cities sprout up everywhere on the ice when the lakes freeze over — shelters, shacks and shanties, encompassing everything from a tarp wrapped around a few poles to massive ‘ice castles’ boasting heat, plumbing, electricity and military-grade fish-finding equipment. But warmer temperatures are putting new pressures on the North’s ice seasons, squeezing them from both ends like a vice: the lakes are icing up later in the fall, and the ice is breaking up earlier in the spring.

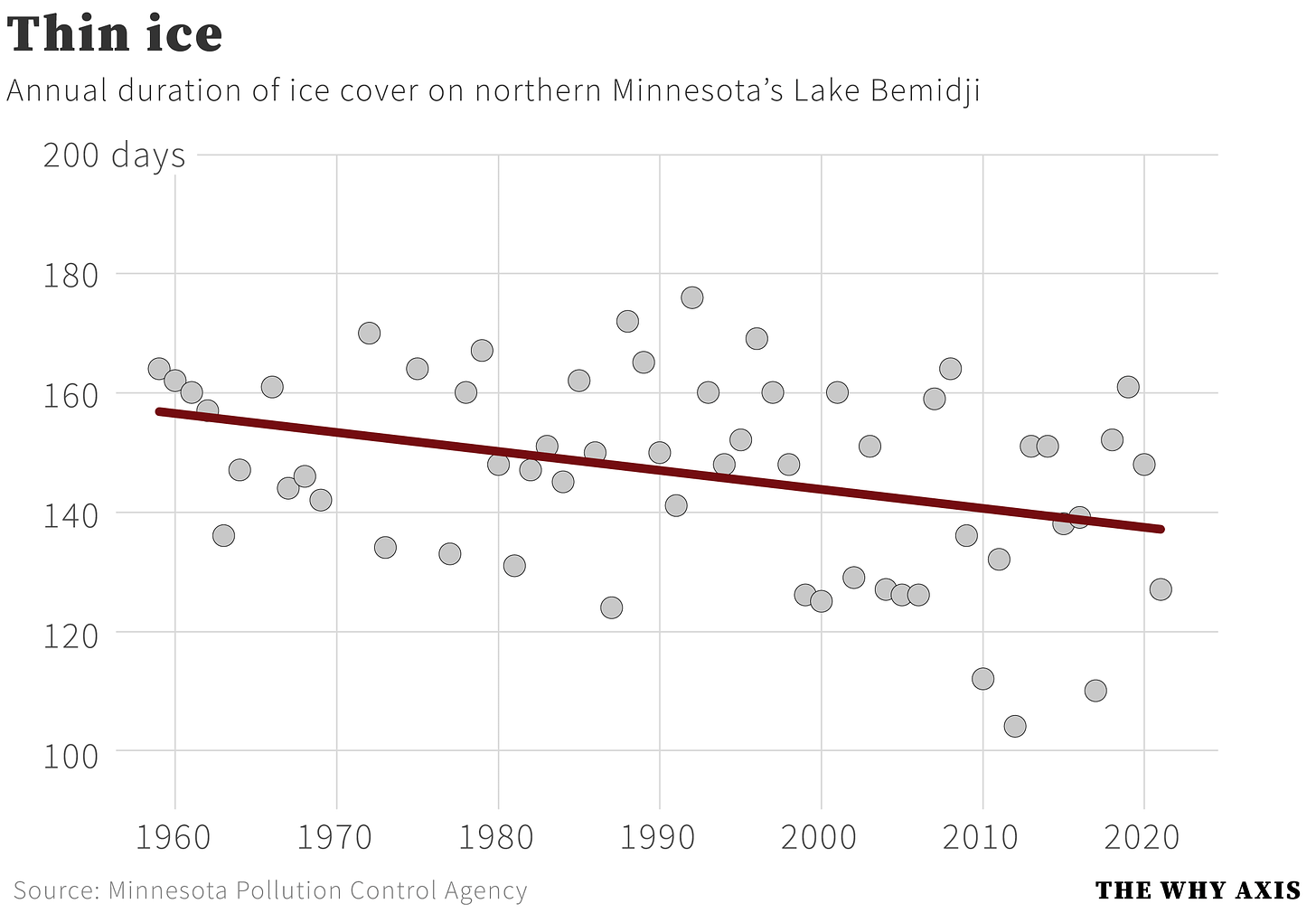

Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources and Pollution Control Agency have been tracking ice-in and ice-out dates on the states lakes for decades. In December, just a few weeks before the accident that took John Klasen’s life, they compiled that data into a report showing that since the 1960s, ice season has shrunk by an average of two weeks across the state. The bulk of that shift is happening at the start of the season, with ice-in dates moving later by about 9 days.

Lake Bemidji, as it turns out, has been one of the hardest hit in the state — it’s lost roughly 19 days of ice, or nearly three weeks, since 1957.

The annual data, in the chart above, shows that the ice season is not only shrinking, it’s also becoming more erratic: in the 1960s, for instance, the length of ice season varied by about 25 days over the decade. In the 2010s, on the other hand, there were more than 50 days’ difference between the shortest and longest seasons. The ice is becoming less predictable.

Sheriff’s deputies responding to the Klasen accident told local media that the ice on the lake came in about two weeks later than expected this year. In any given year, ice-in is driven mostly by the year’s weather patterns, which are in turn driven in part by changes in the long-term climate.

Globally, last year was one of the hottest on record. And places like northern Minnesota are warming even faster than the global average. Since the turn of the 20th century, Minnesota’s Beltrami County — where Lake Bemidji is located — has warmed at nearly twice the rate of the rest of the United States, according to a 2020 analysis by the Washington Post.

One of the reasons climate change is such a tricky problem from a policymaking standpoint is that its impacts are diffuse and abstract, from the typical family’s viewpoint: it’s a lot easier to care about layoffs at the local factory than fluctuations in global carbon dioxide. But global warming is nevertheless making life on Earth more difficult, in thousands of little unseen ways that add up, day by day, year by year. Things grow imperceptibly worse in ways you don’t notice in the moment, but then one day you look up and realize that the oceans are on fire, or that there are tornadoes in December, or that the air is full of smoke, or that a truck unexpectedly fell through the ice.

I honestly don’t know what we can do about any of this. But it’s increasingly becoming clear that all the sacrifices individuals have been asked to make over the years — from tracking our carbon footprints to turning down the thermostat to buying paper straws — aren’t adding up to enough.

Tackling climate change - the extensive damage that greedy & corrupt humans brought upon us all - would require significant policies and laws to change everything humans do. Such change would have to be put into place by governments and every single person would have to abide by the changes.

Unfortunately, humans do not have the capacity to make such change on the scale required. Greed always wins out over sacrifice and change for the good of all. Humans still kill each other, individually and with war, for profit. The rich not only whine about paying their fair share of necessary societal costs but do everything possible to weasel out of doing so.

Look at our government- two people are allowed to bring everything to an absolute halt - one for her ego and the other for his greed and ego. No voting rights, child care credits, climate change policies. Why would anyone think humanity would ever work together to save the planet the richest countries have willingly and greedily destroyed?