Why there's $50 million for doulas in Build Back Better

The New York Times’ Jonathan Weisman published an op-ed masquerading as a news story yesterday, examining some of the “niche” provisions in the recently-passed Build Back Better deal. The story drips with contempt for things like e-bikes, tree planting and money to support local news. But Weisman saves the brunt of his condescension for $50 million in funding earmarked for doulas — non-medical professionals who help expectant moms navigate labor, delivery, and the general complexities of the American health care system.

Weisman notes that “many obscure provisions may emerge as subjects of ridicule” before discussing how “doulas — the word means ‘servant’ in Greek — typically lack formal obstetric training and provide care such as massage and other touch therapy, rather than medical services. They are used by only a small percentage of pregnant women in the United States.” He adds that “the Democrats who secured the doula funding in the hulking social policy bill do not duck their responsibility for it” — as if the provision were an embarrassment that Democrats would try to avoid.

In reality, the evidence on doulas’ effectiveness is strong enough that groups like the March of Dimes “support increased access to doula care” and recommend that they be covered by health insurance.

“Studies suggest that increased access to doula care, especially in under-resourced communities, can improve a range of health outcomes for mothers and babies, lower healthcare costs, reduce c-sections (cesarean sections), decrease maternal anxiety and depression, and help improve communication between low-income, racially/ethnically diverse pregnant women and their health care providers,” the group writes in its position statement on doulas. Support from doulas appears to be critically important in minority communities and in places with poor health outcomes in general.

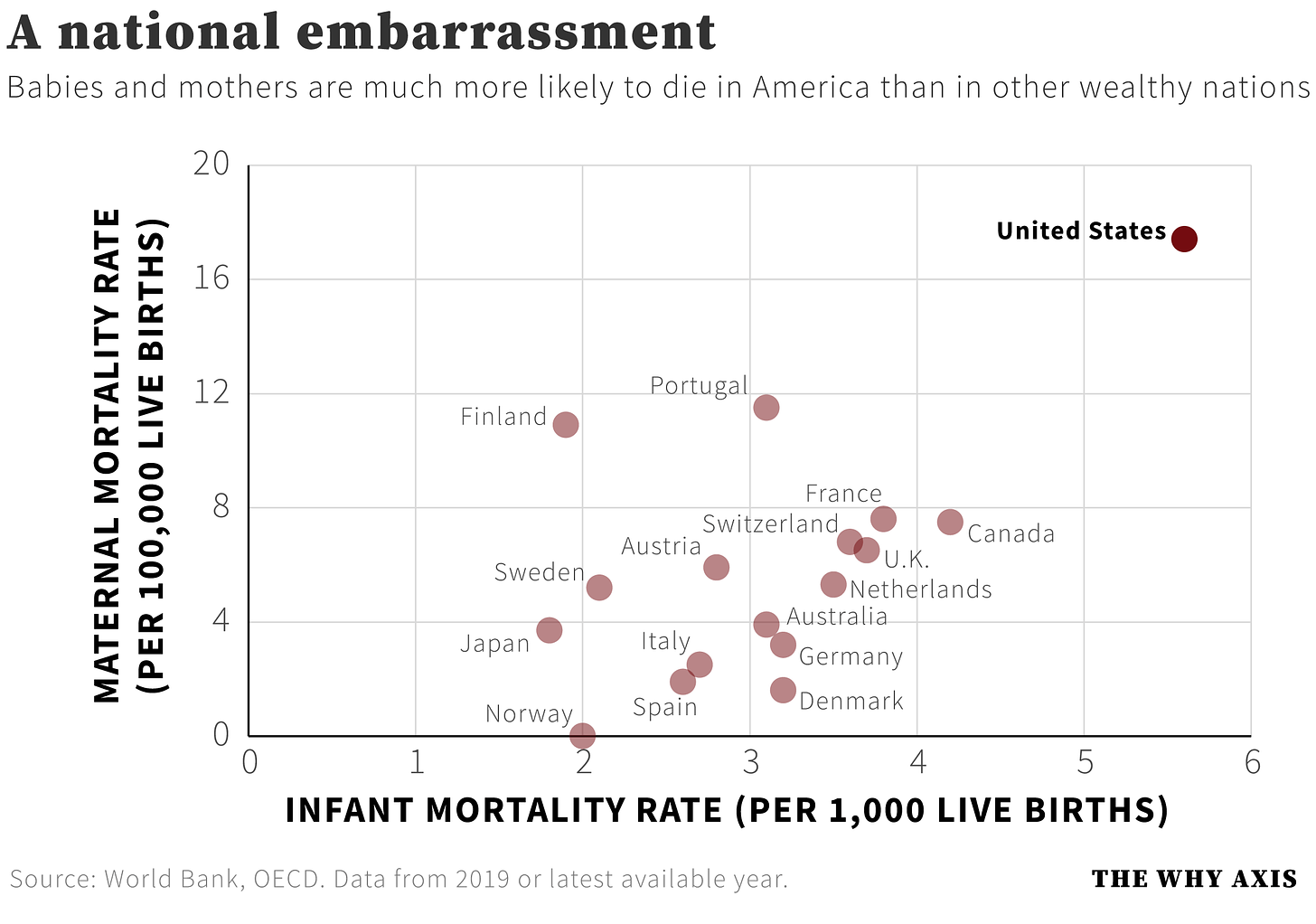

In terms of evidence-based approaches to improve infant and maternal health during childbirth, in other words, it’s hard to do better than increasing access to doulas. And it’s almost impossible to overstate the need for better outcomes: American women are far more likely to die in childbirth than women in other wealthy nations, and American infants are much more likely to die during their first year of life.

The chart above plots infant and maternal mortality for the U.S. and 16 rich nations commonly regarded by public health researchers as our “peers.” We are very clearly an outlier along both axes. Norway, for instance, recorded no maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births in 2019. In the U.S., by contrast, 17 moms were killed in childbirth for every 100k births. The situation for infants is similarly grim, with the odds of death in the first year for American babies running roughly twice as high as the chances for infants in our peer countries.

These numbers should shock you. We are the wealthiest country in the world, yet we consign hundreds of babies and mothers each year to preventable and often agonizing deaths. We have the resources to bring these numbers down close to zero, but for political reasons we choose not to. We choose death.

It’s worth pointing out that these average numbers mask staggering disparities. Black women, for instance, are more than three times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. And black babies are more than twice as likely as white ones to die before reaching their first birthday. College-educated black women are more likely to die in childbirth than white women with only a high school degree. Those disparities are making the U.S. the only nation in the developed world where maternal mortality is rising.

If you were to go to a policy lab and try to design an intervention tailor-made to reduce those disparities and improve those overall mortality numbers, you’d be hard pressed to come up with a better solution than increasing the availability of doulas. Something to keep in mind when you read the mocking words of reporters who don’t really understand what the stakes are.