What the mainstream press can learn from Joe Rogan

New data shows media mistrust near all-time highs, but there's a way to fix that

Reflecting on recent efforts to get podcast host Joe Rogan kicked off Spotify for spreading Covid misinformation, New York Times reporter Matthew Rosenberg made a pretty solid observation. “Joe Rogan is what he is,” he said. “We in the media might want to spend more time thinking about why so many people trust him instead of us.”

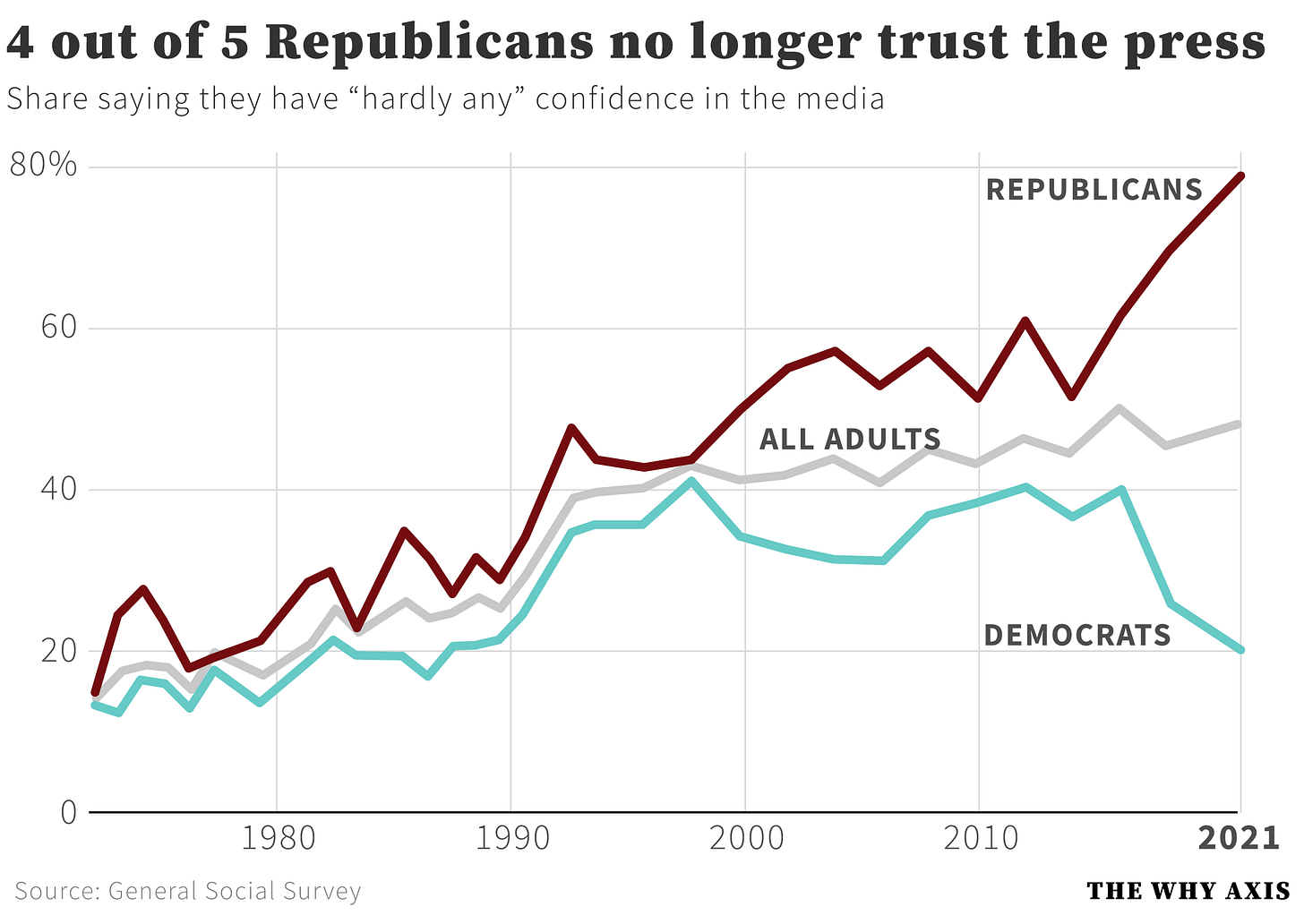

Indeed, the latest data on trust in the media, released last week by the General Social Survey, paints a dire picture. Confidence in the press continues to erode, with those saying they have “hardly any” trust now outnumbering those with “a great deal” of it by roughly five to one. An additional 40 percent of respondents say they have “some” trust.

It wasn’t always this way. Back at the dawn of the 1980s most people said they had “some” trust, while those reporting a great deal of trust still outnumbered the doubters. But over the subsequent decades those numbers began to shift. The story of declining faith in the media is a well-known one at this point. It was driven in large part by the rise of a partisan conservative media, including talk radio and Fox News, that worked relentlessly to discredit mainstream press reports that undermined conservative orthodoxy. These efforts were abetted by conservative politicians who quickly realized that sowing distrust in the press was an effective way to neutralize negative coverage.

That partisan dimension is on plain display when you look at trust by political affiliation.

Since 2014, the share of Republicans saying they have hardly any trust in the media skyrocketed from 51 to 78 percent, easily the highest reading on record. Democrats, meanwhile, became more trusting of a mainstream press that grew increasingly skeptical of Trump’s abuses of power: since 2016, the share of Democrats saying they have hardly any confidence has fallen by half. All told, a partisan confidence gap that was essentially non-existent as recently as the late 1990s has grew to nearly 60 percentage points.

The conservative press critics were (and remain) correct about one thing: most of what we consider the mainstream press — the New York Times, the Washington Post, network news, CNN — has a definite liberal bias. But this isn’t surprising, or even necessarily a problem. Most national news gets produced in the country’s big cities, and people who live and work in those cities tend, for various reasons, toward liberal politics.

Our present moment of media discontent owes to what the conservative critics and the mainstream outlets did with this information. Conservative media treated liberal bias as a scandal, a shortcoming that needed to be eradicated, and falsely (and with a stunning amount of cynicism!) portrayed themselves as the neutral, unbiased corrective to mainstream news.

This caused leaders at mainstream outlets to make a grave mistake: they accepted the proposition that “bias” was a deficiency that can and should be removed from all coverage, rather than a quantity inherent in any human endeavor, and worked feverishly to erase all evidence of a point of view from their stories.

Over the next several decades as conservative media became more partisan, more emotionally charged and more angry, mainstream outlets doubled down on the “view from nowhere,” casting triumphs of the human spirit and brutal atrocities in the same bland, judgment-free prose. The bias wasn’t eliminated, of course: the political leanings of reporters and editors influenced everything from the stories they chose to tell, to the people they chose to interview, to the quotes they chose to include. Rather, the bias was simply covered up: instead of being transparent about the reporting process and the values that necessarily guide it, the press pretended they were simply holding up a neutral, uncaring mirror to the world.

Readers and viewers aren’t dumb: they understand this, and they know that a story produced by the New York Times is going to be very different than something on the same topic from Fox News. But the motives driving Fox are much more obvious than the motives behind the typical NYT story. News consumers like that — they like to know which point of view a story’s coming from.

That brings us back to Rogan, and his particular appeal. CNN’s Brian Fung — a former colleague of mine at the Post — lays it out plainly: “Rogan's appeal, particularly in the age of ‘do your own research!!1!11!’ is that his process and motives come across as transparent to the audience. He shows his work, even if he is extremely credulous about the results. Rogan exudes authenticity because he starts from a position of curiosity. It works because he brings the audience with him on his journey of discovery.”

Contrast this with the opaque process driving the typical NYT or Washington Post White House story — where do these stories come from, and what questions did the reporters start with, and who was feeding information to them, and how do the reporters feel about the information they’re passing on? We hardly ever know the answers to questions like these about political coverage, and until we do — until the mainstream press is more comfortable with acknowledging its own biases and discussing its process — I suspect the picture on trust in the media will remain grim.