Parched

The West's water is drying up

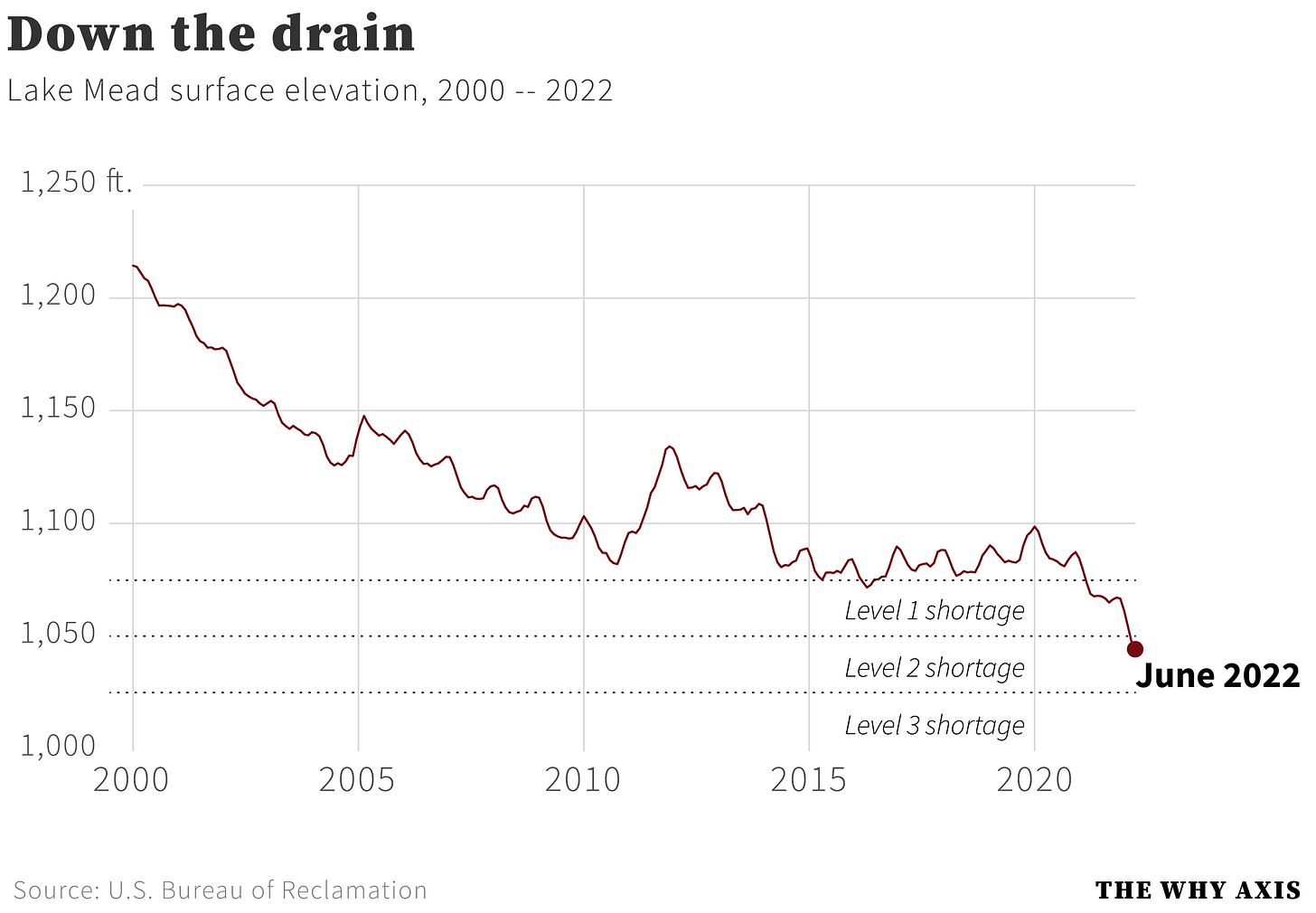

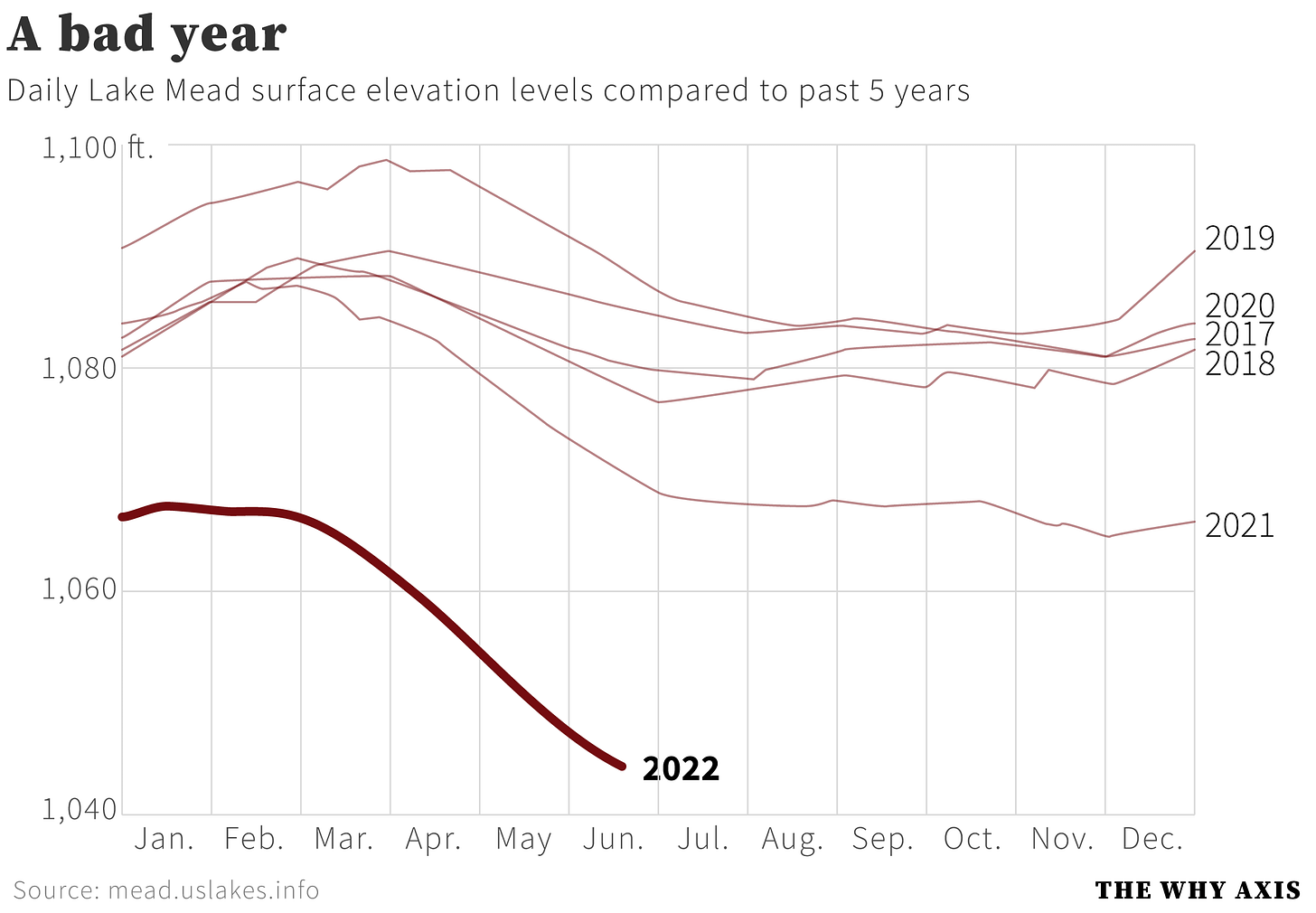

Last month the water level in Lake Mead fell below 1,050 feet for the first time since the completion of the Hoover Dam in 1935, according to the federal agency overseeing the lake. The grim milestone put the lake, which supplies water and electricity to millions living in the western U.S., at Level 2 shortage status, triggering major restrictions on water use in those areas.

The dropoff, currently happening at a rate of roughly 1 foot per week, is occurring more rapidly than regulators anticipated. As recently as last October, the federal Bureau of Reclamation projected the water level would remain above 1,050 feet through the end of 2022. The agency further estimated there was a 16 percent chance of falling below that level in 2023.

Instead, that threshold was reached just seven months later.

In February of this year, Reclamation estimated a 0 percent chance that water levels would fall below 1,020 feet in the 2023 water year. When they re-ran the numbers in May, the odds shot up to 40 percent.

“The Colorado River Basin is in the 23rd year of a historic drought,” Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton told the Senate last week. “Both Lake Powell and Lake Mead – the two largest reservoirs in the United States – are at historically low levels with a combined storage capacity of 28 percent.”

In order to avoid the reservoirs hitting “critical levels,” Touton said, western states would need to slash their use of Colorado River water by up to 4 million acre-feet in 2023 — roughly equivalent to California’s entire annual allotment.

Lake Mead supplies drinking water to roughly 25 million people in the American southwest, as well as water for power generation, industry and agriculture. Nearly all of that use is now threatened. “What has been a slow-motion train wreck for 20 years is accelerating, and the moment of reckoning is near,” said John J. Entsminger, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, at the hearing.

Conceptually the west’s water problem is a simple one: humans are draining the Colorado River faster than it can replenish itself via rain and snowpack, a problem compounded by the ongoing drought. But this is fundamentally not a problem of cities being too big, or populations being too high, or families doing too much laundry. Entsminger’s testimony points to the real culprit: desert farms.

“Around 80 percent of Colorado River water is used for agriculture and 80 percent of that 80 percent is used for forage crops like alfalfa,” he said. Stop and sit with that one for a minute. Eight out of every ten gallons that flows down the Colorado gets diverted to farms and ranches. And most of that gets turned into alfalfa for use not by humans, but by cattle.

Western farmers, in other words, are pumping precious water hundreds of miles around the desert in order to grow plants and animals that cannot otherwise survive there — especially during a multi-decade drought. It’s profoundly wasteful, a practice untethered from a reality that has finally caught up with it.

The optimistic case for the southwest is that these dire conditions force a rethinking of how agriculture is practiced in the region, leading to water savings that put the river on a more sustainable footing. A couple winters of record snowpacks could go a long way toward replenishing water levels on Lake Mead.

But the warming climate is putting a giant thumb on the climatological scale, making that outcome ever less likely. I’m not sure what the less optimistic case is, but we appear to be barreling toward it.

So, consequences have finally caught up to human arrogance and greed. Will humanity face this reckoning with humility, discipline and common sense based changes?

Hahahahahahahahahajahahaha. As if.