One chart that explains the GOP's embrace of authoritarianism

It's hard to win when your policies aren't popular

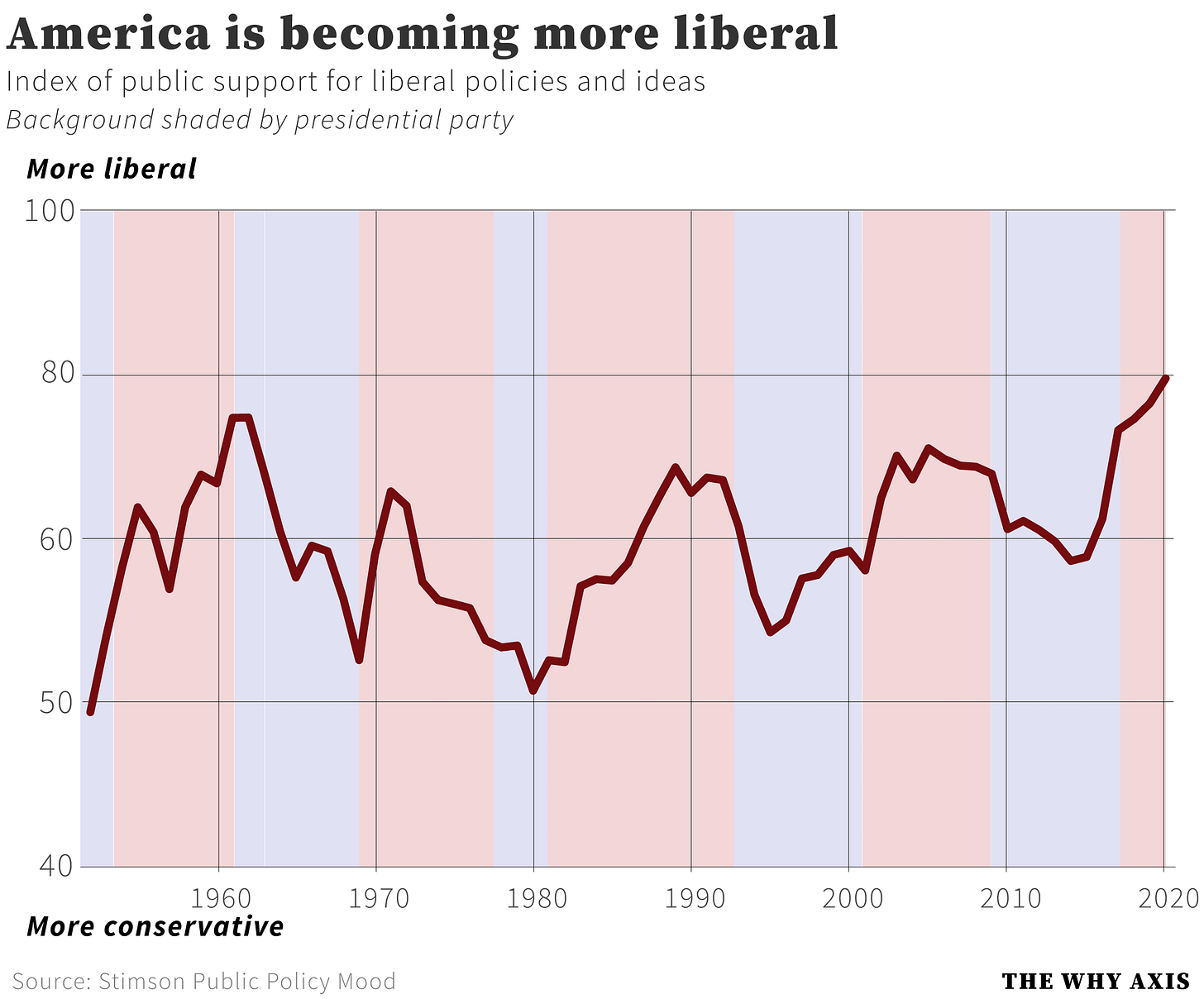

Here it is: your decoder ring for unlocking the secrets of why the Republican Party is abandoning small-d democracy and embracing the principles of authoritarian governance in 2021. It’s a measure of “policy mood” — the general conservative or liberal tilt of public opinion -- in the United States going back to 1952.

This dataset was developed and maintained by James Stimson, an emeritus professor of political science at the University of North Carolina. Stimson basically takes a whole mess of public opinion survey results — on things like the proper role of government, attitudes toward taxation, feelings on social issues like abortion and gay marriage, and more — and mashes them up in a statistical blender to derive an index that can characterize the general tenor of political sentiment in a given year.

The nice thing about this approach is that it provides you with consistent data that’s fairly comparable from year to year. It basically lets you put your finger on the pulse of American politics from the 1950s to today.

Stimson’s latest data, released over the summer, show that the Trump years propelled Americans to greater heights of liberal sentiment than ever before. It’s an iteration of a pattern seen over and over again: when Republican presidents are in office, the public tends to become more liberal. When Democrats are in the White House, the opposite happens. Political scientists refer to this as “thermostatic” public opinion — we are basically a country of contrarian assholes, and when our leaders tell us to do one thing we tend to respond by doing the exact opposite.

But what’s really interesting here is the long-term pattern: the picture since 1980 isn’t one of fluctuation around a steady baseline, but rather consistent movement in a more liberal direction. It’s particularly notable because in recent years Stimson took public opinion on racial issues out of the equation: the trend there was toward more liberal beliefs across the board, and it was biasing the numbers upward. I’m honestly not sure that’s the right call given the ongoing centrality of race to the political discussion, but it’s striking that the numbers look the way they do even without race.

Which brings us to the GOP. Traditionally, when a political party’s messages aren’t resonating with voters that party changes its platform to more closely align with public opinion. The Republican party is certainly in such a place today: Donald Trump’s political agenda of tax cuts for the rich and aggressively racist nationalism was popular with a certain type of aggrieved white voter but that’s about it. Generally speaking Americans want tax hikes on the rich, more spending on social services, universal health care, and liberal social policies, like gay marriage and legal weed. That’s why the line in that chart is going up. And those positions are, emphatically, not what today’s Republican party is offering voters.

But rather than moderate their policies to gain more support, Republicans are trying a different tack: if you can’t win elections, then change the rules of the game until you can. This is the best way to understand recent developments like efforts to suppress voting in Texas and Georgia, the nationwide push for voter ID, the bananapants delusional claims about “rigged” elections and voter fraud, the shambolic “election audits,” the efforts to put partisan legislatures in control of ballot-counting, the aggressive gerrymandering, and more.

These are the actions of a party that knows its agenda is unpopular, but is willing to burn democracy down to get what it wants anyway. The GOP is in an incredibly dark place right now, and despite Joe Biden’s sunny predictions to the contrary Trump’s departure from the White House hasn’t “caused the fever to break.”

Things are going to get worse before they get better. Leaders in the Republican party have shown little concern over what might happen when the gap between public sentiment and legislative action becomes untenable: populations prevented from enacting policy at the ballot box often end up bringing about change by other, more violent means.