This week the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago released the 2022 edition of its Air Quality Life Index (AQLI). The Index takes satellite-derived air pollution data — specifically on fine particles known as PM2.5 — and uses it to calculate how much longer someone in a given region would live if pollution were brought down to the World Health Organization’s current guideline of 5 micrograms per cubic meter.

They’re able to do this because there’s an astonishingly consistent relationship between fine particle pollution and mortality: for every 10 microgram increase in sustained PM2.5 exposure, your life is shortened by about a year. Of note: in the U.S., annual average PM2.5 levels vary by about 20 micrograms depending on which region of the country you live in.

The headline finding of the AQLI: worldwide, lives are cut short by an average of about 2 years due to PM2.5. “This impact on life expectancy is comparable to that of smoking, more than three times that of alcohol use and unsafe water, six times that of HIV/AIDS, and 89 times that of conflict and terrorism,” the group behind the project writes.

But there’s tremendous variation, between countries and within them, on the health impacts of air pollution. The situation is particularly bleak in India, where ambient pollution levels continue to rise in defiance of global trends. There the average citizen’s life is cut short by five years. In the capital city of Delhi, the burden is an astonishing 10 years.

“Over the last two decades, industrialization, economic development, and population growth have led to skyrocketing energy demand and fossil fuel use across the region,” the authors explain. “In Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan combined, electricity generation from fossil fuels tripled from 1998 to 2017. Crop burning, brick kilns, and other industrial activities have also contributed to rising particulates in the region.”

Here in the U.S. the situation is considerably less grim, due largely to the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970. The AQLI estimates that law is responsible for a life expectancy boost of 1.4 years since 1970, with people in cities like Washington D.C. seeing boosts exceeding 3 years.

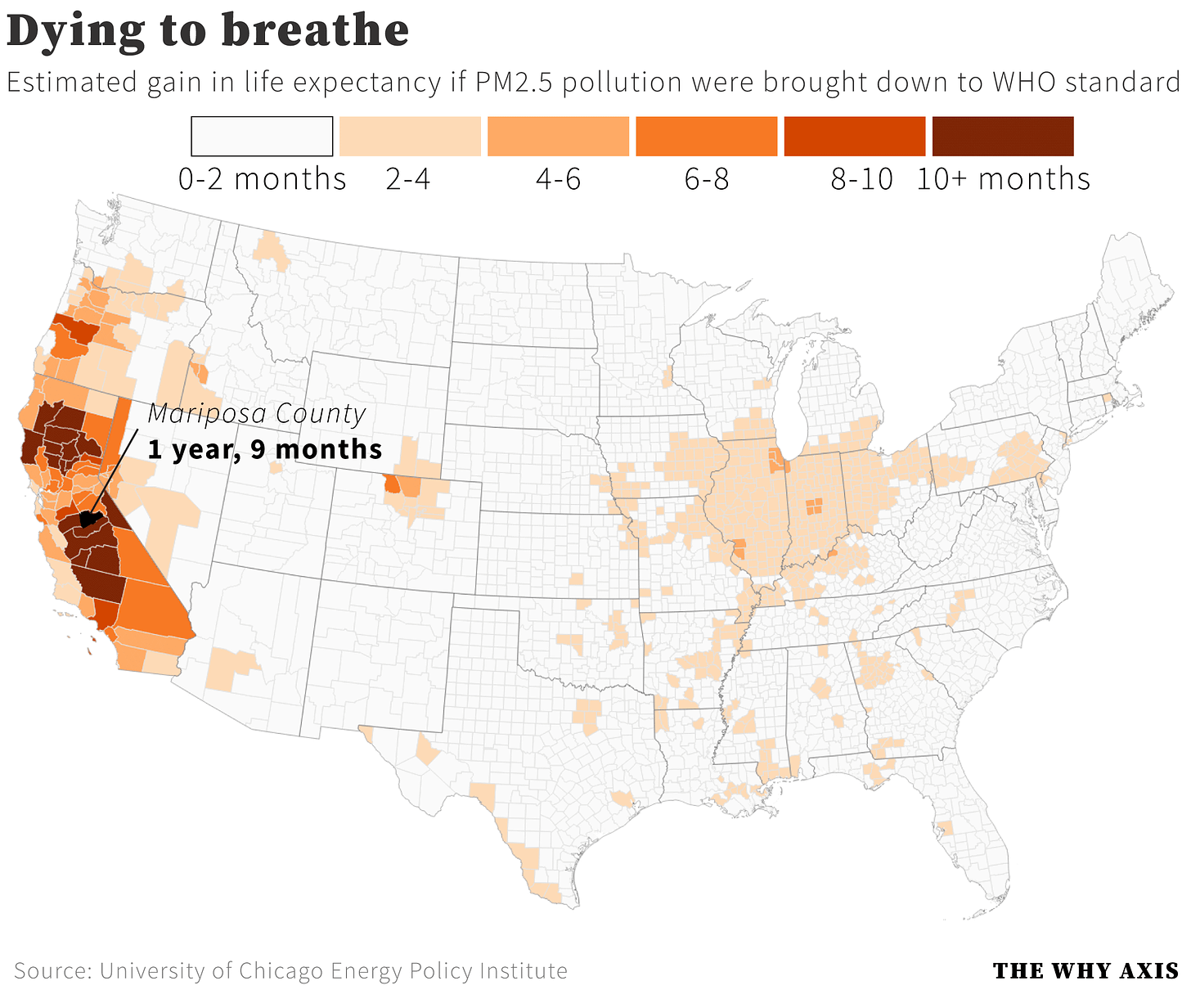

Today, the researchers estimate that fine particle pollution shortens the average American’s life by between two and three months. But again, the effects are unevenly distributed: people living in most areas of inland California are losing closer to a year of life due to that region’s notoriously dirty air. Other hotspots include wildfire zones out west, as well as midwestern states like Illinois and Indiana.

Overall the American picture may not seem too bad, particularly compared to places like India. But it’s worth bearing a couple points in mind.

First, the AQLI only considers PM2.5 pollution. While those small particles are the leading driver of air pollution mortality worldwide, other sources — including nitrogen oxides and ozone — are significant risk factors as well.

Second, the AQLI’s data is satellite derived. This is extremely useful because it provides apples-to-apples coverage across the globe, in regions and countries where ground-based pollution monitors don’t exist. But monitor readings are more accurate, and in many cases show higher average levels than the satellite measure. In the U.S., for instance, AQLI’s satellite data shows a national average PM2.5 concentration of 7.1 micrograms per cubic meter in 2020. EPA’s monitor network, on the other hand, yields an average of 8.1 micrograms for that year — a 14 percent difference. While the AQLI does incorporate this monitor data into its models, the difference is still worth noting.

Finally, the AQLI model specifically measures outdoor, rather than indoor pollution levels. This is because comprehensive data on indoor air quality is virtually nonexistent — satellites can’t see inside your home, and environmental agencies typically don’t install air monitors in peoples’ houses. The model driving the AQLI does include data on a region’s total pollution emissions, from sources like smokestacks and chimneys and cars, which provides some reflection of things like smoke from indoor wood fires. But indoor air quality can differ dramatically from outdoor air, and we spend most of our lives indoors. So how that all works out in the end, from an effect-on-longevity standpoint, is kind of an open question.

Still, I like the AQLI a lot because it kind of flips the standard air pollution mortality calculation on its head: rather than ask how many people die in a given year due to air pollution, it shows how pollution is shortening almost all of our lives, right now.

Air pollution's drastic impact on life expectancy is alarming. The worrisome decrease in quality of air is a ticking health time bomb. We must act swiftly https://depositphotos.com/vector-images/pointing-finger.html, adopting cleaner technologies and sustainable practices, to ensure a healthier future for generations to come.👉🏼🌍🔗