How rom-com plots have changed over the past four decades

Big data, actually

Today’s newsletter is about some fascinating new data published just in time for sappy holiday rom-com season: A pair of researchers at SUNY Buffalo applied sophisticated machine learning techniques to 40 years’ worth of romantic comedy scripts to analyze how the genre has changed over time, and what it might say about Americans’ views on love.

The researchers, Melissa Moore and Yotam Ophir, grabbed the scripts of the 188 highest-grossing romantic comedies since 1980, as tracked by Box Office Mojo. That list includes familiar titles like My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Something About Mary, Knocked Up, and Sweet Home Alabama. They then basically had a computer go through the scripts and attempt to deduce, from the characters’ conversations, the major topics and themes the films deal with.

“A huge motivation for this project was to better understand how this genre depicts romance,” Moore explained via email. “I watched these films a lot when I was growing up, and so do many others.”

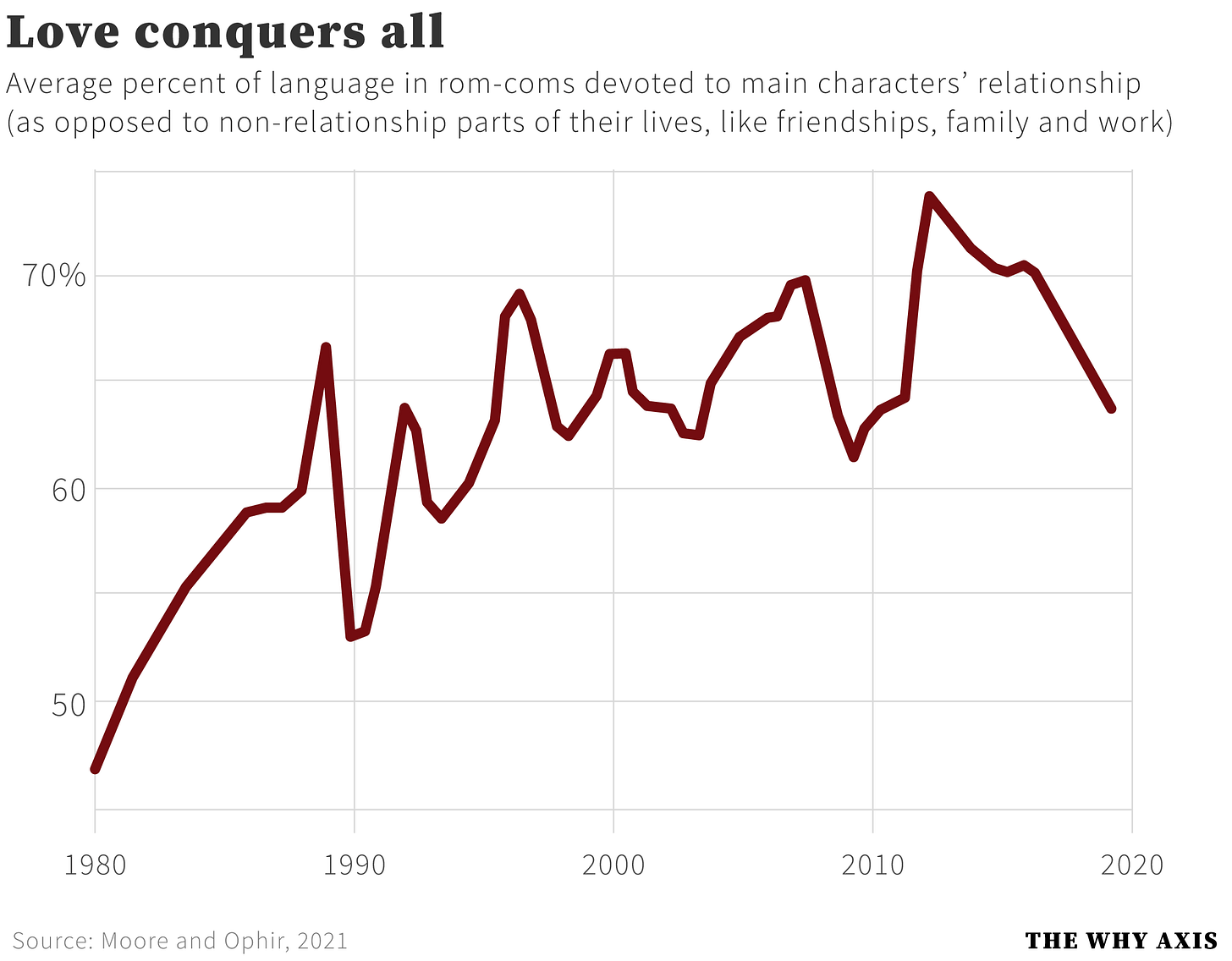

They found, first of all, that since 1980 rom-coms have been putting more and more emphasis on the rom: the proportion of the average rom-com script focused solely on the relationship between the two leads (as opposed to work, friends, and other non-relationship parts of their lives) is growing considerably.

“This trend shifts screen time away from areas such as professional life, day jobs, and business, toward an even stronger emphasis on the dynamics of courtship and romantic relationships,” the authors write.

Via email, lead author Melissa Moore said she thinks of 1987’s Overboard as a quintessential 80s-style romantic comedy: “A crazy premise [wealthy heiress cheats carpenter out of money, gets amnesia, carpenter tells her he’s her husband, they eventually fall in love] with a lot to think about other than ‘will they or won't they.’” By contrast, she thinks of Crazy Rich Asians as an exemplar of modern romantic comedy: “Huge emphasis on not only the protagonists' relationship, but that of their families. Lots of disagreements and obstacles as well,” she said.

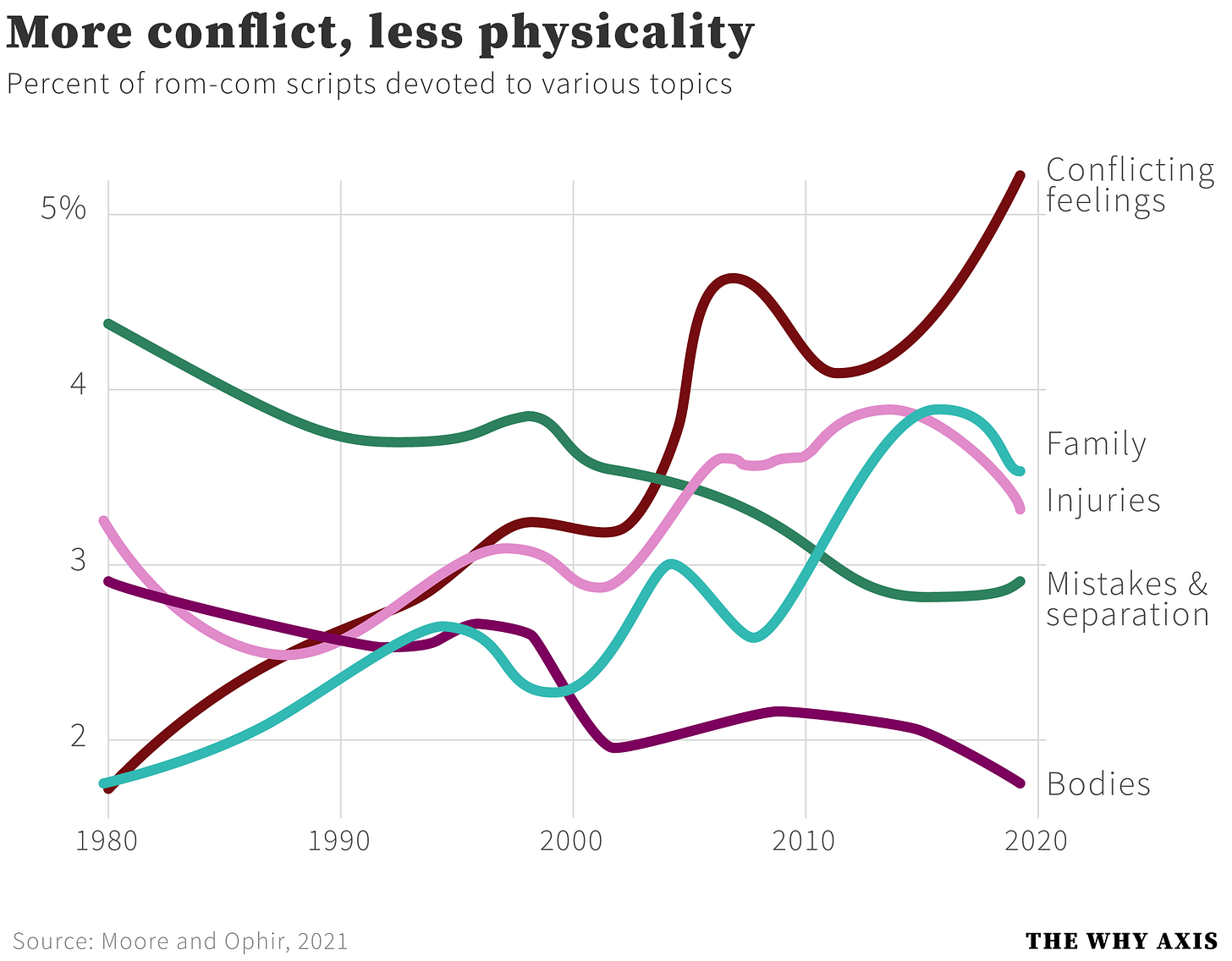

Second, the ways rom-coms depict those relationships are changing too. Scripts show a growing emphasis on conflicts and mixed feelings between the two main leads. These topics deal with “dissident experiences including liking someone as more than a friend, simultaneous gestures of thanks and apology, feeling seen but invisible, and being in a bad mood despite having fun,” the authors explain. The scenes typically “involve unbalanced partnerships, with one partner ready to commit while the other hesitates” — think, for instance, of basically the entirety of the plot of Knocked Up.

Scripts are also devoting more space to physical injuries and hospital scenes — likely a source of comic relief — while focusing less on the physicality of the leads — legs, butts and other markers of physical beauty.

“These changes reveal romcoms as an increasingly tumultuous depiction of courtship,” the authors conclude. “Compared to viewers in the 1980s and 1990s, modern audiences should expect more and higher hurdles for protagonists to overcome, with more physical injuries and trouble that may involve their families or children (planned and unplanned, biological and adopted).”

The authors suspect the growing portrayal of conflict and mixed feelings as central elements of modern romance may be giving audiences skewed perceptions of how relationships should work. “These depictions tell audiences that the experience of falling in love is inherently uncomfortable, and their persistent and increasing use may cultivate unhealthy relationships depictions in young audiences’ minds.”

Via email, Moore said that “the way [rom-coms] depict love isn't always healthy-- taken out of context, a lot of the ‘romantic’ behaviors are undesirable or unrealistic (Do you really want a love interest to send you gifts even when you haven't given them your address? To stand outside your house and play a boombox? To make you dress in a certain way? Would you forgive someone for lying about who they are?).”

One open question is whether and how much the thematic changes identified in rom-com scripts are a function in industry-wide shifts in how films are written and produced. Conflict, after all, is a key element of any good movie plot. Producers and studios could be increasingly demanding scripts with sharper conflicts across the board. Moore notes that in general, films with a greater emphasis on romantic relationships do better at the box office.

But regardless of the root cause, the central finding nevertheless stands: the relationships we see in the movie theater are increasingly grounded in conflict, mixed feelings and uneasiness. Are those on-screen relationships holding up a mirror to what’s happening in society, or are social norms following film depictions, or both or neither? It would be interesting to trace, for instance, whether and how changes in film romances track with real-world indicators like divorce rates and teen pregnancies (on that latter point, other research has already shown that media depictions play a considerable role).